Beginning of the main content.

Next tab will go to the map. Use this link to skip the station map.Ghost Towns and Canneries: A Journey Along the Skeena

Riding the train from Smithers to Prince Rupert in northwestern British Columbia is as much a trip back in time as it is a way of getting from A to B. The route largely follows the mighty Skeena River as it flows to the ocean, the main artery of travel and commerce for centuries, and the names flashing past on remote signposts beside the tracks represent communities and often entire industries that have almost been swallowed up by the forests and the sea.

The Hazeltons

A couple of hours outside of Smithers on the westward journey, the train pulls into a small community called New Hazelton, located near the confluence of the Bulkley and Skeena Rivers. In the 1890s however, paddle-wheeled steamboats were the best way to get inland, making Old Hazelton, a short distance away, the main action around. That all changed in 1911, when the Grand Trunk Pacific Railroad was being laid. Squabbling between the provincial government, the railway company, and private speculators about the route led to additional townsites being developed.

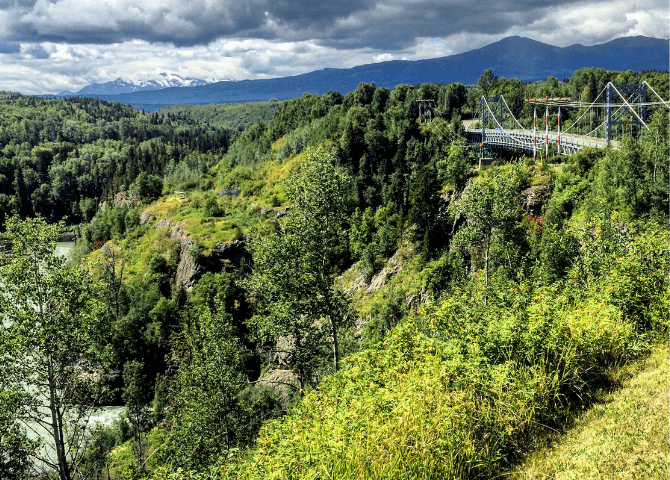

New Hazelton may have ended up with the train station, but Old Hazelton’s historic downtown wins the charm award, with its pioneer-style buildings and the small Anglican church that dates back to the 1880s. Nearby, the Gitxsan First Nation village of ‘Ksan is a spectacular heritage site with totem poles and longhouses situated where the Bulkey flows into the Skeena. A walk across the dizzyingly precipitous suspension bridge at Hagwilget Canyon is also not to be missed.

From Mining Town to a Two-Person Retreat

After Hazelton, the train winds along the south bank of the Skeena River before crossing to the north side just before the Gitxsan village of Gitsegukla. Here, archaeologists have dated ancient village sites to more than six thousand years old; local oral tradition reaches back for thousands of years more. As the train rolls through the next village of Gitwangak, keep an eye out for a line of totem poles, some more than a century old, that rise among the houses. There are more than 50 poles to be seen in the area; famously, Emily Carr visited in 1912 to paint some of them.

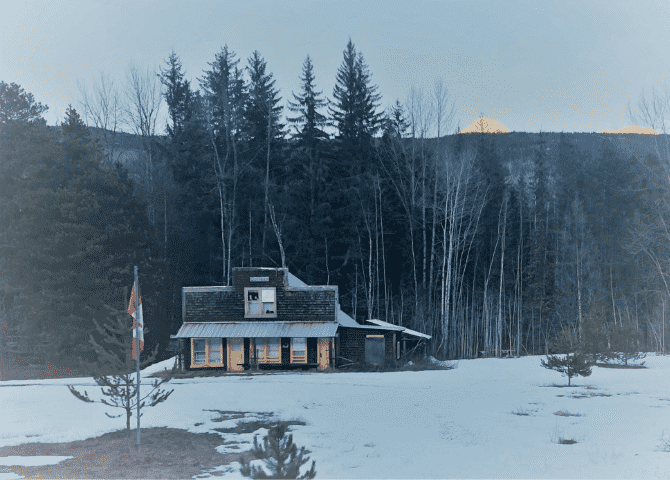

Dorreen, located about 90 km west of Hazelton and accessible only by train, is one of the few remaining pioneer settlements of its kind in the north. Up until about the 1930s, powered by a small gold mine nearby and a seasonal lumber industry, Dorreen was a thriving little place; today, although Dorreen is officially marked as a station, only the original general store and telegraph office* remains to be seen on the south side of the tracks. There are just one or two full-time residents year-round and the train only stops if one or the other of them is getting on or off.

A Train Station on the Move

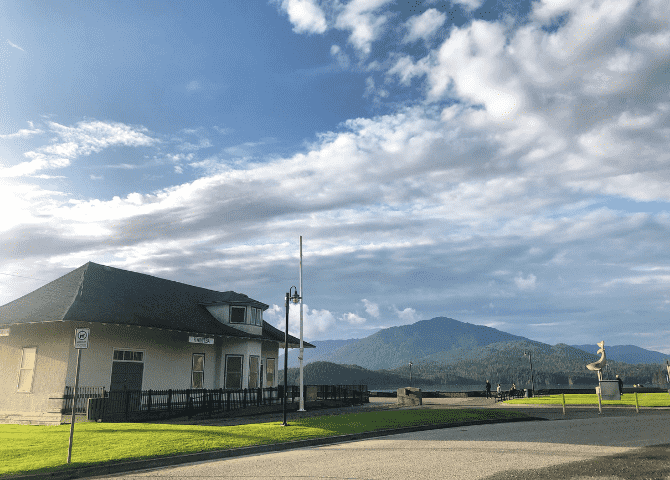

Past the city of Terrace, approximately half way on your journey, the Skeena river widens right out and the tidal influence of the Pacific Ocean becomes apparent. At certain periods of the day, mudflats full of migrating birds stretch out towards the water; rows of rotted wooden pilings flash past outside, marking long-vanished stations and work camps. At Kwinitsa, about 80 km from Prince Rupert, a classic CN Rail station and foreman’s house used to stand beside the track, one of ten stops between Rupert and Terrace in the rail line’s early years. In 1985, the City of Prince Rupert salvaged the little station building, barging it down the Skeena and right into the Rotary Waterfront Park, where it’s used as a museum today.

A few kilometers further along, just before the Tyee Overpass, the train slows down so passengers can catch a glimpse of Tsimshian pictographs painted on the rock wall close beside the track. These images were discovered by an archaeologist from a passing train in 1925, and although they must have had significance when they were created, their precise meaning has been lost over time.

From 26 to 2: Restored Canneries in the Lower Skeena

The Skeena was frothy with activity from the 1880s on, when salmon canneries began to proliferate like mushrooms in the forest after a rain. These remote operations had to be self-sufficient, with shipwrights, bunkhouses and stores clustered along the waterfront, connected by boardwalks. As the train follows the curve of land into Inverness Passage, more of those old pilings and glimpses of machinery are often all that has survived. However, there are two notable exceptions.

Cassiar Cannery ran from 1903 to the mid-80s, processing fish and shipping it south to market. In early 2006, new owners began to restore the remaining heritage buildings; you can arrange for the train to stop and drop you off and spend a night or two in one of several guesthouses with names like Coho, Halibut, and Sockeye. A little further along, the 130-year old North Pacific Cannery is now a National Historic Site and offers tours and accommodation in the renovated bunkhouse on site.

Much has changed in the more than one hundred years since trains began running along the Skeena River; once-important industries have faded from the scene, and entire communities vanished with them. Historic glimpses of old ways of life still remain beside the tracks, however, adding a rich facet to the journey that makes it unlike anywhere else in the world.

Header photo: North Pacific Cannery. Credit: Northern BC Tourism/Mike Seehagel

Plan your trip

Find the best fares for your destination and let the train whisk you away.

Please wait while we fetch the best offers.

*Prices valid for either direction. One-way fare in Economy class, excluding sales taxes. The number of seats is limited.

Fares may vary based on selected day of week and time of departure. Check conditions for more information.

Lowest fare conditions

ROUTES :

Available on VIA’s network.

REFUNDS AND EXCHANGES :

Escape fare tickets are non-exchangeable and non-refundable. View our Fares and Conditions page for details.

SEAT AVAILABILITY :

The number of seats is limited.

Read more